The tactile image is a knowledge medium capable of making all forms of 2D representations accessible in a non-visual way.

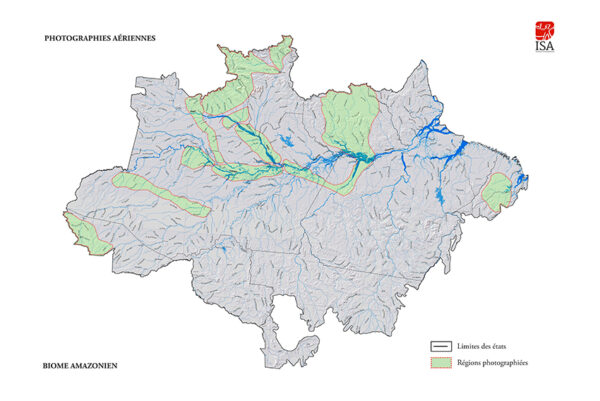

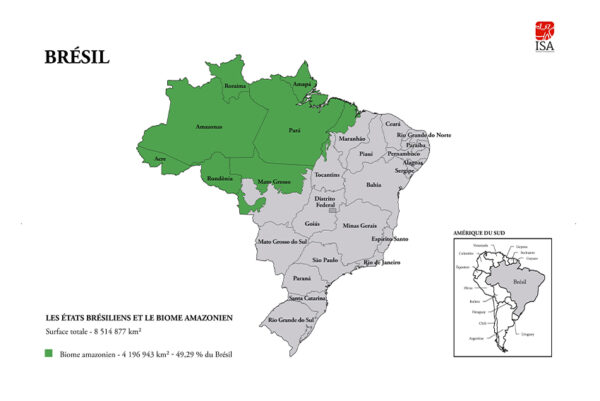

Thanks to the support of the Crédit Mutuel Alliance Fédérale Foundation, the VISIO Foundation has embarked on a world first: making photographic art accessible to the visually impaired through the AMAZÔNIA TOUCH tactile audio case. Their support allowed the production of 550 copies of this case which includes 18 photos and 3 geographic maps transcribed in 21 boards in relief. These guides, which can be consulted on this site, have been designed to explain each photo, accompaning the fingers in their tactile discovery and reading of the work.

Thus, the use of the tactile image allows blind and visually impaired readers to acquire a graphic culture with which they are able to have access to artistic works and architectural heritage masterpieces.

The AMAZÔNIA TOUCH tactile cases will allow the establishment of tactile reading learning workshops for blind or visually impaired people, teachers and professionals specialized in the accompaniment of people with visual disabilities.

These workshops will be led by Hoëlle CORVEST, an expert in the field of tactile images for over 30 years.

For more information, contact us at +31 (0)2 41 68 15 18.

Paraná connecting the Rio Negro and the Cuyuní River. State of Amazonas, 2019 Located in northwest Brazil, Amazonas is the state with the largest surface area in the country. It is bordered to the north by Colombia and Venezuela, and to the west by Peru. The paranás are similar to lakes, and are connected to the great rivers by natural channels called “furos”.In periods of high water, lakes and large rivers tend to merge, as if the river was widening.

Adão wearing an eagle feather headdress and a face paint made from the genipa tree fruit. State of Acre, 2016 The portrait of this man, named Adão, was taken by Sebastião Salgado in the village of Nova Esperança, located in the indigenous territory of the Yawanawá of the Rio Gregório. The Yawanawá people speak Pano. They are proud of their name, which means “people of the peccary.” This animal, close to the wild boar, is one of the most feared in the forest.

The Yawanawá live in the heart of the Amazon but have been decimated by colonizers and imported diseases. They were enslaved due to the exploitation of rubber, and forcibly evangelized. They recovered their land in the 1990s. Until 2014, their population in Brazil was estimated at 813 people. Members of this group can also be found in Bolivia and Peru.

One of the most remarkable aspects of their ancient traditions is the feather art: the Yawanawá create some of the most elegant ornaments in the entire Amazon, most often made of white eagle feathers, an animal sacred to them, such as the type of headdress worn here by Adão, whose face is covered with paint made from plant pigments.

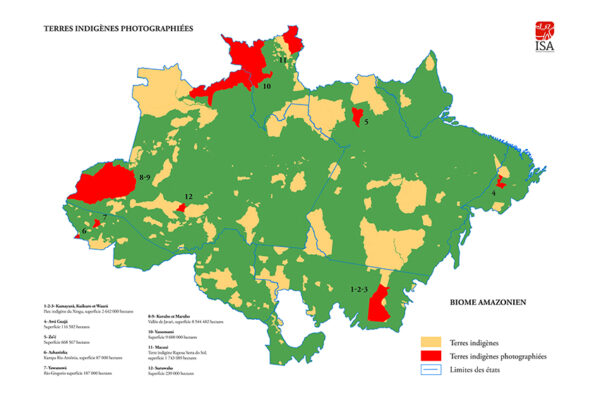

Brazilian states and the Amazon biome This map shows the entire Brazilian territory with its 27 states, distributed over a total area of over 8.5 million km². It is divided into two areas:

• The right part (in grey) includes the North-East, the South-East, the South and the South-West regions as well as half of the Center region. Most of Brazilian’s states are concentrated there.

• The left part (in green) covers the North, the West and the other half of the Brazilian Center region. There are fewer states there. Two of them, however, are the largest ones in area: the states of Amazonas and Pará, occupying almost 1/3 of the country’s total territory.

Together with the states of Acre, Roraima, Amapá, Rondônia, and part of Mato Grosso, Maranhão and Tocantins, they constitute the Amazon biome.

The Amazon biome covers an area of 6,700,000 km² across several countries. It includes the Amazon rainforest, an area of dense rainforest, and other ecoregions that cover most of the Amazon basin. The biome contains flooded forests, lowland forests, grasslands, bamboo groves, palm groves, swamps and savannah, sand barrens, and alpine tundra. It is throughout this area that Sebastião Salgado will travel for 7 years, photographing its forest, rivers, mountains and people by navigating its waters, and flying over the thick jungle and mountain ranges, as well as staying with the ethnic communities living there, scattered in this biome, in the heart of the largest forest in the world.

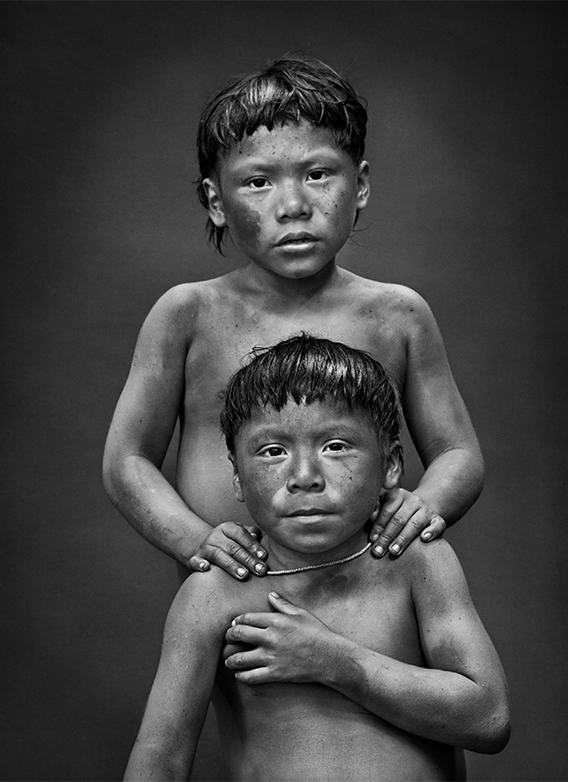

Arsa Kanikit Korubo (in the back) and Txipu Wankan Korubo (in the front). Indigenous territory of Javari Valley. State of Amazonas, 2017 Arsa and Txipu are children from the Korubo tribe. The Korubo is an indigenous group of about 120 people living in two villages on the banks of the Ituì, located in the territory of the Javari Valley, in the western Amazon, near the border with Peru.

The Korubo’s skin is always painted red with a substance they obtain from urucum seeds but it is the color of the mud that gave them their name. They are a people of the highlands, far from the rivers and the mosquitoes that inhabit their banks. When the Korubos approach those banks, they cover their skin with clay to protect themselves from insect stings. Seeing them like this, their neighbors – the Matis – started calling them “Koru-bo”, which means “people covered with clay”. Today they have little contact with other people, and their traditional culture is almost intact. Other than the urucum paint on their skin, the peculiarly cropped hair and the two armbands they eventually put on, the Korubo don’t wear many adornments.

Group of jauari palm trees at the edge of the Jaú River. National Park of Jaú. State of Amazonas, 2019 Jaú National Park, with an area of 23,000 km², is the largest national park in the Amazon basin. Located about 200 km northwest of Manaus, it contains a good proportion of the hydrographic network of blackwater, with its specific fauna and flora. On a single hectare of forest, one can find up to 180 different species of trees. The darkness of the water is due to the acids released from decomposing organic matter and to the low content of land sediments. During the dry season, the rivers turn into white sandy beaches, while the rainy season floods the forests, creating secondary river beds of different sizes, as well as lakes and paranás (river channels separated from the main stream by a strip of land).

The waterways provide a convenient way to move through the sprawling forest. On the Amazon and major rivers, boats act as buses, but to move on to a secondary tributary, travelers must take a motorized dugout canoe capable of crossing the rapids. If it runs into cascades, the passengers have to carry the boat to a safe location upstream. “Traveling through the rainforest is an exhilarating adventure and a privilege, but it is also a challenge, always” Sebastião Salgado reminds us.

Zo’é women paint their bodies with urucum. Indigenous territory of the Zo’é. State of Pará, 2009 In texts from the 16th century, Jesuits referred to a people on the banks of the Amazon River, in the area where the city of Santarém is located today. They described Indians with faces decorated with a wooden cone in the lower lip. This tribe then disappeared, keeping their distance from the modern world until the 1980s, when a group of evangelists met them 300 kilometers north of Santarém. It is said that they owe their name to the first word that the first Indian contacted by the missionaries uttered: “Zo’é”, which means in their language: “It’s me”.

Sebastião Salgado has been close to this tribe: “I went on a long expedition with them, and it felt like a trip to Paradise: two months of walking in the jungle with the Zo’é, during which, in 2009, I was able to visit all the villages where the 300 or so inhabitants live. I followed the families living their daily life, caring for their crops, hunting and fishing, from one end of the territory to the other, as I followed the fishing camps on the Cuminapanema and Erepecurú rivers.”.

Forest landscape in the Mariuá Archipelago, Middle of Rio Negro. State of Amazonas, 2019 This photograph shows an igapó forest; this word refers to forests seasonally flooded by Amazonian waters on the river banks. Similarly to other forests in the tropics, it is common to see only a few dominant tree species, which seems to be the case here. The waters never completely recede; the soil remains spongy. It is an ecosystem where the vegetation cannot actually set its roots down. Very few flowers grow there.

Typaramatxia Awá and Kiripy-tan during a hunt. Awá-Guajá indigenous territory. State of Maranhão, 2013 The Awá-Guajá are an almost isolated indigenous people, with about 450 members living in Maranhão, a state in Brazil that has experienced intense illegal logging in recent decades.

Today, they live in two territories – Upper Turiaçu and Carú – which they share with other ethnic groups – the Ka’apor, Timbira and Guajajara – who have had more contact with the rest of the world. Today, the Awá-Guajá subsist in untouched forest areas and are one of the last hunter-gatherer people in Brazil. They use materials from the forest to build their houses. They collect fruits and honey, and hunt animals such as armadillos, peccaries (a mammal similar to a small boar), coatis (close to raccoons) and monkeys.

The cousins Hahani, Tiniru and Ugunja. Indigenous territory of the Suruwahá. State of Amazonas, 2017 The Suruwahá have chosen to live in almost total isolation and have preserved their cultural traditions. For these reasons, they are the indigenous people who probably resemble the most to the ones that the first Europeans encountered when arriving to Brazil. Their population is of around 150 individuals and it is increasing (they were 100 in the 1980s).

The Suruwahá speak a language from the Arawá family, as do several other groups inhabiting the same area. In the early 1980s, fishermen, hunters and rubber tappers (people who extract latex from the tree barks by cutting it) began to threaten the region. This indigenous territory was certified in 1991. Since the early 2000s, the Suruwahá have benefited from the “No-contact” policy. In order to be allowed to meet them, Sebastião Salgado had to undergo twelve days of quarantine, like all other visitors, to ensure that he was free of any transmissible disease. This portrait of three girls was taken at the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health, near the Pretão River.

Marauiá mountain range. Indigenous territory of the Yanomami. Municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. State of Amazonas, 2018 The Upper Rio Negro, where the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira is located, is situated in the heart of the Amazon Basin, in a trinational border area comprising Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela. The region was annexed late to the Portuguese Brazil: the first contacts between the Indians and the Portuguese took place only in the 17TH century, the mouth of the Rio Negro being identified and described only in 1639. This marked the beginning of a profound demographic drain on the Amerindian populations, which were either captured and enslaved – around 1750, an estimated 20,000 captives were deported – or decimated by smallpox or measles epidemics. The Brazilian traders settled after 1830. The rubber boom at the end of the 20TH century increased the pressure on the indigenous labor force, which was forcibly moved to areas with rubber trees, resulting in a breakdown of their traditional way of life.

Today, the region is mostly composed of Amerindian territories, known as “Indigenous Lands”, and protected areas, constituting an ecological and cultural corridor, inhabited by several dozen ethnic groups. This vast area is still entirely covered by forest over approximately 350,000 km² and is far from any road infrastructure.

To know more

Credits