Meet the Artist

Sebastião Salgado, a humanist and environmentalist photographer.

Sebastião Salgado was born in 1944 in Minas Gerais, Brazil. He is married to Lélia Wanick Salgado. Trained as an economist, he began his career as a professional photographer in 1973 in Paris. He worked with several successive photo agencies until 1994, when he founded his own agency, Amazonas Images, with Lélia, which is now their studio and is exclusively dedicated to their work together.

Sebastião has traveled to more than 100 countries for his photographic projects, which have featured in numerous publications in the international press, as well as published in several books, all designed by Lélia Wanick Salgado, among which stand out Sahel, Man in Distress, in 1986, The Hand of Man, in 1993, Terra Genesis, in 2013, Gold, The Gold Mine at Serra Pelada, in 2019 and Amazônia, in 2021. Traveling exhibitions of these works are still presented to this day in major museums and galleries on all continents. Lélia Wanick Salgado is the designer and curator of all these exhibitions.

There have been many books and films dedicated to the photographer’s life and career, such as the book From My Land to The Planet, in 2013, by journalist Isabelle Francq; and, in 2014, the documentary film Salt of the Earth, co-directed by Juliano Ribeiro Salgado and Wim Wenders. This film received the Special Jury Prize at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard category, as well as the César for Best Documentary Film in 2015; it was also nominated for the 87th Academy Awards in the United States.

Salgado’s latest photographic project presented here is about the Brazilian Amazon and its inhabitants. The objective of this work is to try to make them known and draw attention to the threats facing the forest and the indigenous populations: illegal forest exploitation, gold mining, hydraulic dams, cattle breeding, soybean farming, as well as the effects of climate change, which is having a growing impact on the continent.

This work was presented to the public in May 2021 in the form of a book and a first exhibition at the Philharmonie de Paris entitled AMAZÔNIA.

Sebastião Salgado recently declared on the radio France-Culture: “You can become a part of any community. I take a lot of time to create my pictures. It takes time for that split second to occur. The hardest thing is to go, to leave your comfort zone and your safety and go to the depths of the Sahel or elsewhere. Once you are willing to leave your comfort zone, to float away, you are accepted.”

Salgado has received numerous awards for his work, including an Honorary Membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institut de France.

Sebastião and Lélia have been working since the 1990s on the environmental reconstruction of a part of the Atlantic Forest in Brazil, in the state of Minas Gerais. A large parcel of land they owned became a nature reserve in 1998. In the same year, they created Instituto Terra, whose mission is reforestation and environmental education.

Discover the work

Paraná connecting the Rio Negro and the Cuyuní River. State of Amazonas, 2019 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

Located in northwest Brazil, Amazonas is the state with the largest surface area in the country. It is bordered to the north by Colombia and Venezuela and to the west by Peru. The paranás are similar to lakes and are connected to the great rivers by natural channels called “furos.” In periods of high water, lakes and large rivers tend to merge, as if the river were widening.

Adão wearing a headdress made of eagle feathers and face paint made from the fruit of the genipa tree. State of Acre, 2016 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

The portrait of this man, named Adão, was taken by Sebastião Salgado in the village of Nova Esperança, which is located in the indigenous territory of the Yawanawá of the Rio Gregório. The Yawanawá speak Pano.

They are proud of their name, which means “people of the peccary.” This animal, close to the wild boar, is one of the most feared in the forest.

The Yawanawá live in the heart of the Amazon but have been decimated by colonizers and imported diseases. They were enslaved for the exploitation of rubber and forcibly evangelized but recovered their land in the 1990s.

Until 2014, their population in Brazil was estimated at 813 people. Members of this group can also be found in Bolivia and Peru.

One of the most remarkable aspects of their ancient traditions is feather art: the Yawanawá create some of the most elegant ornaments in the entire Amazon, most often made of white eagle feathers, an animal sacred to them. Such is the type of headdress worn here by Adão, whose face is covered with paint made from plant pigments.

Juruá River, State of Amazonas, 2009 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

With a length of approximately 2,400 kilometers, the Juruá River is one of the largest tributaries of the Amazon. It emerges from the highlands of Ucayali, Peru, before entering the territory of the state of Acre in northwest Brazil. It is navigable for 1,800 kilometers, but as soon as it enters the low and flat lands of the Amazon region, west of Manaus, it becomes agitated and forms a maze of meanders.

Even when they can use the currents, navigators need a lot of effort and patience to cover any distance.

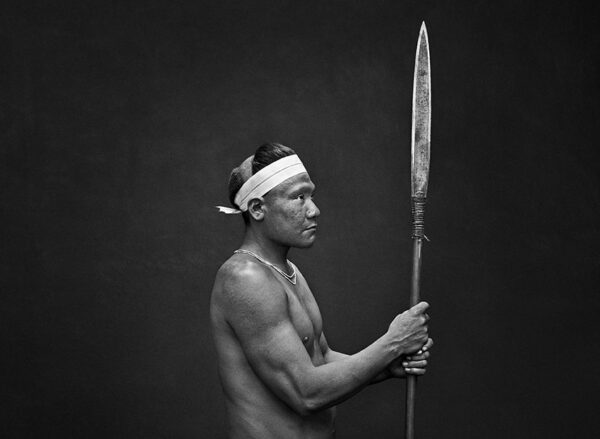

Kamayurá Shamans. Indigenous territory of Xingu. State of Mato Grosso, 2005 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

Located in the southwest of Brazil, in the state of Mato Grosso, the indigenous park of Xingu, with an area of two million six hundred and forty-two thousand hectares, is the country’s most famous indigenous territory. It is inhabited by 6,000 indigenous people, with 16 ethnic groups and languages belonging to 5 main linguistic families. It’s the first large indigenous reserve created to protect several ethnic groups. When the park was created, in 1961, the people of Upper Xingu suffered a demographic catastrophe due to a succession of epidemics.

Sebastião Salgado spent several months in this area to meet three of these communities, the Kuikuro, the Waurá and the Kamayurá, whose population is estimated today at some 600 individuals.

This photo is a group portrait on a black background of eight Kamayurá shaman chiefs, shot in his portable studio in a rather smoky atmosphere.

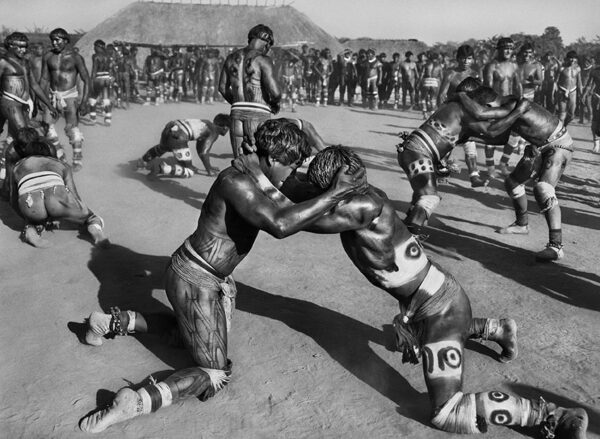

Kuarup festival at a Waurá village: wrestlers in a huka-huka match. Indigenous territory of Xingu. State of Mato Grosso, 2005 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

The indigenous park of Xingu is famous all over the world thanks to the images of its indigenous festivals.

This photo immortalizes a scene from a Kuarup festival, which brings together several tribes around shared rituals.

During these days of ceremonies, the warriors of the various villages confront each other in the huka-huka fight, as in a sporting competition.

Typaramatxia Awá and Kiripy-tan during a hunt. Awá-Guajá indigenous territory. State of Maranhão, 2013 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

The Awá-Guajá are an almost isolated indigenous people, with about 450 members living in Maranhão, a state in Brazil that has experienced intense illegal logging in recent decades.

Today, they live in two territories (Upper Turiaçu and Carú), which they share with other ethnic groups (the Ka’apor, Timbira and Guajajara) who have had more contact with the rest of the world. Today, the Awá-Guajá subsist in areas of untouched forest and are one of the last hunter-gatherer people in Brazil. They use materials from the forest to build their houses. They collect fruits and honey, and hunt animals such as armadillos, peccaries (a mammal similar to a small boar), coatis (close to raccoons) and monkeys.

Forest landscape in the Mariuá Archipelago, middle of Rio Negro. State of Amazonas, 2019 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

Located in the northwest of Brazil, Amazonas is the state with the largest surface area in the country. It is bordered to the north by Colombia and Venezuela and to the west by Peru. This photograph shows an igapó forest; this Portuguese word refers to forests seasonally flooded by Amazonian waters on the banks of rivers. As with other forests in the tropics, it is common to see only a few dominant tree species, which seems to be the case here.

The cousins Hahani, Tiniru and Ugunja. Indigenous territory of the Suruwahá. State of Amazonas, 2017 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

The Suruwahá have chosen to live in almost total isolation and have preserved their cultural traditions. For these reasons, they are the indigenous people who probably resemble most of the ones that the first Europeans encountered when they arrived in Brazil. They number some 150 individuals and their population is increasing (they were 100 in the 1980s).

The Suruwahá speak a language of the Arawá family, as do several other groups that inhabit the same area. In the early 1980s, fishermen, hunters and rubber tappers (people who extract latex from the bark of the tree by cutting it) began to threaten the region. This indigenous territory was certified in 1991. Since the early 2000s, the Suruwahá have benefited from the “No-contact” policy. In order to be allowed to meet them, Sebastião Salgado had to undergo twelve days of quarantine, like all other visitors, to ensure that he was free of any transmissible disease. This portrait of three girls was taken at the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health, near the Pretão River.

Antônio Piyãko’s family. Kampa do Rio Amônea indigenous territory. State of Acre, 2016 The Asháninka form a large Amazonian community, estimated at over 100,000 people. Most of them live in Peru, but 3,000 are in Brazil, in the state of Acre, divided into two communities along the Envira and Amonea rivers. The Europeans who invaded Peru from the 1530s onwards described the Asháninka as warriors in the service of the last Inca nobles who had taken refuge near the Brazilian forest after they had lost their capital, Cuzco. From the end of the 19th century, this region was invaded by tens of thousands of rubber tappers and later by foresters and cattle breeders who pushed them further and further into the forest.

In 1992, the Asháninka obtained recognition of their territory from the Brazilian government. Today they are dedicated to reforestation, fish farming, cultivation of medicinal plants and the development of their traditional crafts. It was on the banks of the Amonea River that Sebastião Salgado visited in 2016, in the village of Apiwtxa. “It is a village, he describes, that seems to have existed there for a very long time. This sense of permanence is expressed in the elements of the culture, such as the clothes, the style of the houses, the food habits or the stories told, where the defeat of the Incas seems to be quite recent.”

Marauiá mountain range. Indigenous territory of the Yanomami Municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. State of Amazonas, 2018 Audio description

Tactil reading audio guides

The Upper Rio Negro, where the city of São Gabriel da Cachoeira is located, is situated in the heart of the Amazon Basin, in a trinational border area comprising Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela. The region was annexed late to Portuguese Brazil: the first contacts between the Indians and the Portuguese took place only in the 17th century, and the mouth of the Rio Negro was identified and described only in 1639. This marked the beginning of a profound demographic drain on the Amerindian populations, which were either captured and enslaved—around 1750, an estimated 20,000 captives were deported—or decimated by smallpox or measles epidemics. The Brazilian traders settled after 1830. The rubber boom at the end of the 20th century increased the pressure on the indigenous labor force, which was forcibly moved to areas with rubber trees, which resulted in a breakdown of their traditional ways of life.

Today, the region is mostly composed of Amerindian territories, known as “Indigenous Lands” and protected areas, constituting an ecological and cultural corridor, inhabited by several dozen ethnic groups. This vast area is still entirely covered by forest over approximately 350,000 km² and is far from any road infrastructure.

Sebastião Salgado presents us with an aerial view.

Explore the universe

Credits

- Photographs : © Sebastião SALGADO

- Exhibition AMAZÔNIA – Original scenography : Lelia WANICK SALGADO

- Accessible exhibition initiated and produced by : the VISIO Foundation

- Project Management : VISIO Foundation & Marie GAUMY

- Design of texts : Sebastião SALGADO – Lelia WANICK SALGADO – Farid ABDELOUAHAB

- Visually impaired proofreader : Hamou BOUAKKAZ

- Voices : Tercelin KIRTLEY & Olivia GOTANEGRE

- Recording : MÉDIAPHONIE

- Interviews – Réalisation : MALSAGECCO PRODUCTIONS

- Translation : Eric CHENEBIER

- Website : MONAGRAPHIC

- Web accessibility consultant : EMPREINTE DIGITALE

More information

- Philharmonie de Paris : 20 may 2021 – 31 october 2021

- MAXXI Rome : 1er october 2021 – 13 february 2022

- Science Museum Londres : 13 october 2021 – march 2022

- SESC Saõ Paulo : 15 february – 3 july 2022

- Science Museum Manchester : 10 may 2022 – august 2022

- Palais des Papes Avignon : june 2022 – october 2022

- Museo do Amanhã Rio de Janeiro : 19 july 2022 – 30 october 2022